Goodhart’s Law is Telling you Something. Are you listening?

Consider this: as the head of a semiconductor or hardware start-up, you must have studied Moore’s law, which predicts the exponential increase in computing power over time. Similarly, as a sales professional, you are likely familiar with the Pareto principle, or the 80-20 rule, which states that 80% of sales come from 20% of customers. Interestingly, you may have applied this principle to your studies when you completed 80% of the work in the last 20% of the semester! Furthermore, if you are a strategy enthusiast, you have probably used Porter’s Five Forces framework extensively in your career. These are just a few laws, frameworks, and guiding principles that business leaders have relied on over the last few decades to spearhead global transformations.

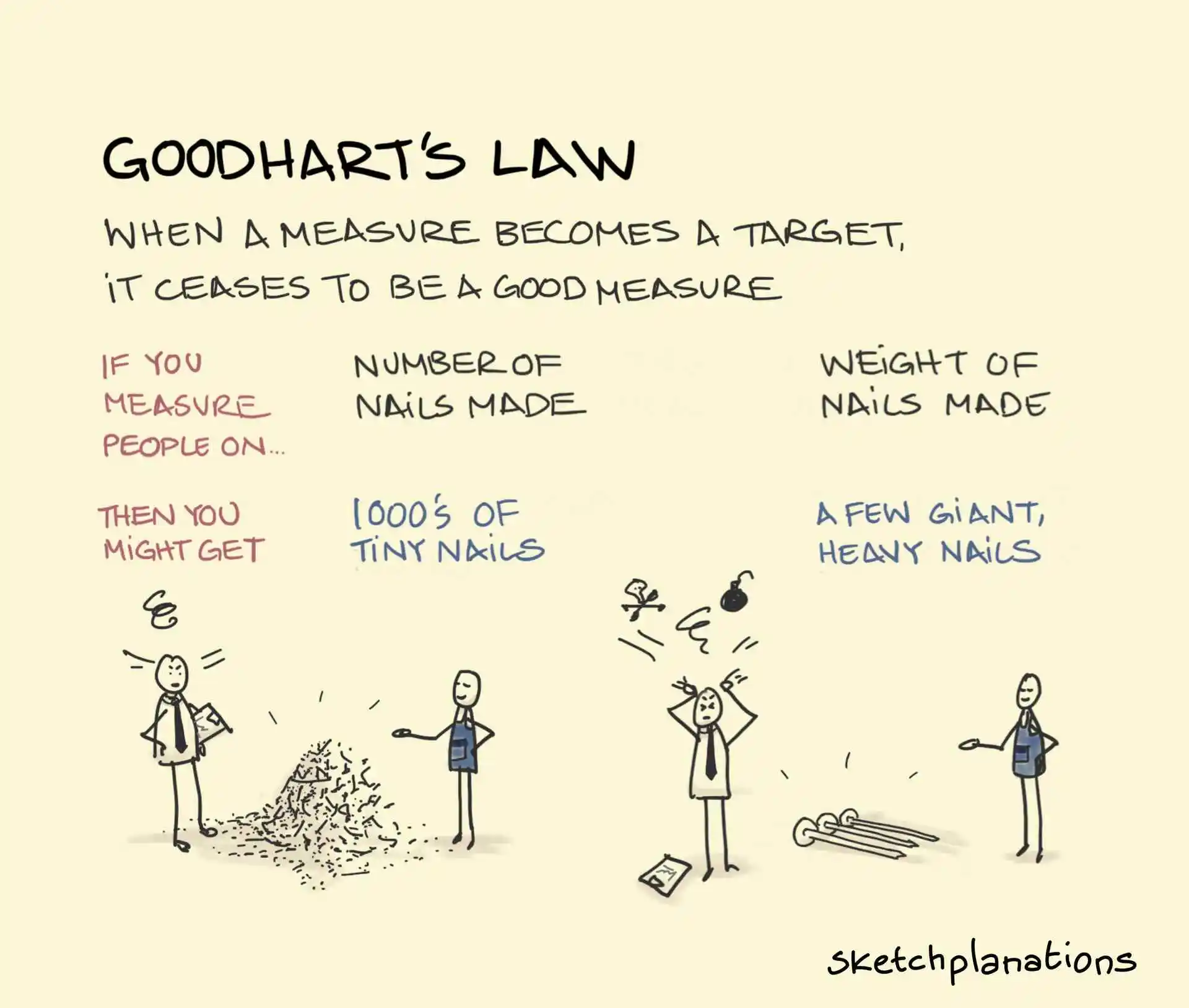

However, one such fascinating principle—that affects almost everything around us—does not receive the attention it deserves. We’re talking about Goodhart’s law, which we’re going to demystify in this article. Named after the famed British economist Charles Goodhart, Goodhart’s law states, “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” This definition is a bit simplistic, but you get the gist of it.

Any observed statistical regularity will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes.

Source: Sketchplanations

Today, data analytics and data-driven decision-making are the big buzzwords. Any strategic decision, be it a business decision or a public policy decision, is more likely to succeed if it is backed by empirical data. That’s all very logical, but if we are going to rely on metrics for decision-making, we need to be mindful of Goodhart’s law.

Ignoring this aspect can prove costly later, as evidenced by quite a few failed businesses—start-ups and established companies alike. Often, the root cause of failure may be attributed to other dependent aspects such as failed strategies, inability to read market transitions, inability to move fast enough, wrong product-market fit, and so on. However, dismissing the possibility of Goodhart’s law playing a part may be premature.

The Pervasiveness of Goodhart’s Law

The effects of Goodhart’s law can be seen across various sectors. In the healthcare sector, for instance, hospitals and clinics often use patient satisfaction scores to evaluate performance. When these scores become targets, healthcare providers might focus excessively on improving patient satisfaction at the expense of actual health outcomes. Similarly, in the education sector, standardised test scores are often used to measure school performance. When these scores become targets, schools might “teach to the test”, neglecting broader educational objectives.

When it comes to digital media, YouTube algorithms are designed to maximise watch time and engagement. When these metrics become targets, content creators might produce sensationalist or clickbait content to meet these targets, compromising the quality of information. Similarly, in the field of Search Engine Optimisation (SEO), websites might use black-hat techniques to improve their search rankings, ultimately degrading the user experience.

Goodhart’s Law in Action: The Volkswagen Scandal

“We’ve totally screwed up,” conceded Volkswagen America’s former CEO, Michael Horn, in the wake of the “diesel dupe” scandal.

In September 2015, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued a notice of violation of the Clean Air Act to the German automobile conglomerate Volkswagen Group. The US agency conducted studies which revealed that between 2009 and 2015, over 482,000 VW cars in the US alone (& 11 million worldwide) came fitted with a “defeat device”. This device allegedly masked or controlled the nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions to pass the regulatory tests in the US, but in fact emitted up to 40 times more NOx pollutants in real-world driving.

After a lengthy legal and ethical stand-off between the two parties, which resulted in two CEOs resigning, a record 12.6 million VW cars being recalled from the market and the stock prices falling by almost a third, the scandal, also known as “Dieselgate”, cost Volkswagen $33.3B in fines, penalties, financial settlements and buyback costs.

Why is this relevant while discussing Goodhart’s law, you may wonder? Well, because the turbocharged direct injection (TDI) diesel engines which were fitted in these 12.6 million cars worldwide were programmed to manipulate emissions in way that they meet the regulatory standards. Since the emission numbers set by the regulatory body became the target, the pressure on Volkswagen was to meet that number, rather than actually creating an eco-friendly vehicle.

In reality, these VW cars were a lot more harmful to the environment than they were marketed to be, and a stamp of approval was sought based on fabricated claims. What this tells us is that Volkswagen was willing to take short-cuts just to satisfy a regulatory metric, overseeing the huge environmental risk and ethics dilemma around it. Along with losing billions in cash and goodwill, the automotive giant also demonstrated how Goodhart’s law could result in unintended consequences for an ambitious project.

The reason that you face Goodhart’s law is that people try to apply methods of measurement designed for measuring passive systems, on systems that fight back.

Goodhart’s Law and Start-ups

Many start-ups rely on digital engagement metrics to track growth. One of the most commonly used metrics is “Monthly Active Users” (MAU). Now, there is nothing inherently wrong with tracking MAU, but the moment it becomes a target, the team responsible for it may feel pressured to inflate it. As a result, start-ups might overspend on digital marketing, use bots to increase followers on social media, or engage in other practices that artificially boost engagement numbers. This problem can be exacerbated in a culture that emphasises “results at any cost”.

Consider a sales team run on targets. If an account team lands a bumper deal one year, the year-over-year (YoY) growth for their account the following year will likely not be the same. If the organisation uses YoY growth as a metric to measure the account team’s performance, they might avoid such bumper deals in the future to prevent setting unattainable targets. This example highlights how Goodhart’s law can lead to unintended consequences in performance measurement.

Implications for Decision-Making

The principle of Goodhart’s law extends beyond mere metrics and targets. It emphasises the importance of context in decision-making. Metrics are essential for tracking performance and making informed decisions, but they should not become the sole focus. It is crucial to understand the underlying factors that drive these metrics and to consider the broader implications of setting specific targets.

One way to mitigate the risks associated with Goodhart’s law is to use a balanced scorecard approach, which considers multiple performance indicators and their interrelationships. This approach provides a more holistic view of performance and reduces the likelihood of overemphasising any single metric. Additionally, promoting a culture of transparency and accountability can help to ensure that targets are pursued in an ethical and responsible manner.

In summary, data driven decision making is the right way and using metrics for performance tracking is unavoidable. But adequate care must be taken to ensure you don’t fall in the trap that Goodhart’s law warns us about.

Have you witnessed or experienced Goodhart’s law in your personal/professional life? Let us know in the comments below!

A version of this article was originally published in IIA Ventures.

Responses